We’re burned out from the election.

Our internet feeds are filled with cute animals, soft pillows, and dance videos (yes, I even posted footage from the 1980 World Disco Dancing Championships) to combat election fatigue – “because election fatigue is real, y’all” as USA Today’s headline about puppies suggests.

Why are we burned out? Because we’ve endured 20 months of 24-hour media coverage, rarely interrupted by non-election news. Because we’ve endured and even participated in heated political debates which included slammed fists, silent walkaways, ALL CAPITALIZED RESPONSES ON FACEBOOK AND TWITTER, adjectives we thought we had thrown out in elementary school (“stupid,” “idiot,” “liar,”) or ones we didn’t realize were politically palatable (“hitler,” “nazi,” “fascist,”), all in the guise of advocating for – or against – who we thought might be a more “trustworthy” and “capable” President of the United States.

We disagree and we don’t know how to talk civilly to each other about it.

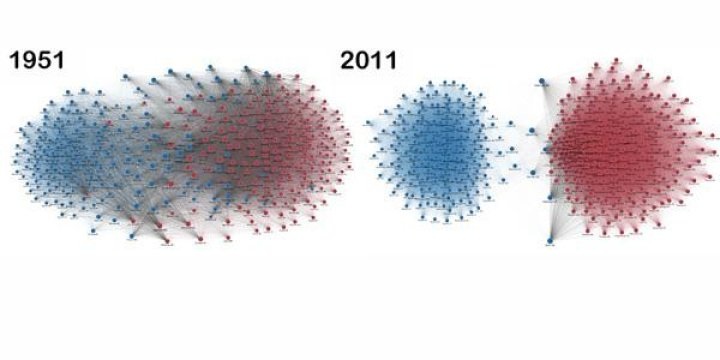

From our neighborhoods to the halls of congress, we don’t collaborate – let alone talk – with those who think differently from us. Research supports the media analysis that congress has become increasingly polarized over time. A striking visual representation of this has been making the rounds online, published initially by PLOS One:

[“This image illustrates the US House of Representatives in 1951 and 2011. Republicans are in red, Democrats in blue. Nodes are members. Edges are a relative measure of bill voting cooperation.”]

As Terry Madonna, director of the Center for Politics and Public Affairs at Franklin & Marshall College describes, “Thirty and 40 years ago, (political leaders) disagreed with each other, but they didn’t think the republic was in peril. That’s the apocalyptic view that each side has of the other. … They literally think in those stark terms.”

Scholars describe the reality that “[2016] is the year we all decided once and for all that those on the other side … didn’t just hold different opinions, but were out to destroy the country and everything it stands for.”

This idea - that a person with an opposing viewpoint aims to destroy the country - reflects the heightened tensions and violent rhetoric heard across the country. Several school districts even decided to close for election day for safety reasons.

We’ve lost our neighbors in echo chambers and ideological silos.

Making worse this polarization is our ideological separation which means that very few of us have the opportunity to speak with someone who disagrees with us, let alone to do so in a civil manner.

This separation is variously described by scholars and analysts as echo chambers, filter bubbles, and ideological silos, and is consistent with increased residential segregation. Cass Sunstein, in his 2001 book Republic.com, describes the “echo chambers” created by the internet where “people restrict themselves to their own points of view—liberals watching and reading mostly or only liberals; moderates, moderates; conservatives, conservatives,” etcetera. Not only do we self-restrict, but web-generated algorithms steer users to these echo chambers, or into “filter bubbles,” limiting our consumption of diverse viewpoints.

Pew Research has found that this separation extends into our relationships as well. For those who consistently identify with a party, most of their close friends also share their political views. Those relationships are also sometimes a product of our geographical residences – where we live, which according to scholars is increasingly segregated along class and race lines. That segregation in itself impacts not only our ideological silos, but power and policy:

“Segregation of affluence not only concentrates income and wealth in a small number of communities, but also concentrates social capital and political power. As a result, any self-interested investment the rich make in their own communities has little chance of “spilling over” to benefit middle‐ and low-income families. In addition, it is increasingly unlikely that high‐income families interact with middle‐ and low‐income families, eroding some of the social empathy that might lead to support for broader public investment in social programs to help the poor and middle class.”

So we live in isolated bubbles, get fed perspectives which only support our own, and in turn develop heated and at times violent rhetoric towards those who may see things differently than us. In other words, we’re becoming less compromising, less cooperative, and less able to see different perspectives – the core skills needed to resolve conflicts and live productively in a democracy (or family, or workplace, or faith community, or anywhere with another human being).

Where to start? A simple challenge

We sometimes forget that everyone prefers a more peaceful, more collaborative world over a divisive and destructive world when given the option. One of the most fundamental skills in building peace is being able to see, hear, and ultimately understand diverse viewpoints on divisive issues. So how do we move beyond our natural and increasing polarization and separation to have the opportunity to see, hear, and understand a different perspective from our own? A few simple ideas may get us going in the right direction:

- Read a physical newspaper (even better – read several which you know lean different political directions). This escapes the algorithms fed online to only deliver news that you will agree with.

- Attend a community gathering organized by people you don’t know. It doesn’t even have to be political in nature, but you’ll be allowing an opportunity for face-to-face interaction which builds trust, community, and appreciation of difference.

- Wonder out loud. When you hear a perspective you disagree with, press “pause” on your defensive reactions and wonder out loud, why it might be that they hold that perspective.

- Listen. When in conversation with someone with a different viewpoint – seek to understand their perspective first before you offer your ideas. Listening – and understanding – are radical skills that are foundational to cultivating a more peaceful world.

- Practice forgiveness and patience. We’re quick to create enemies based on radically opposing viewpoints. What if instead we were patient enough to listen to the viewpoint, and even forgive each other when we say things that are hurtful or rude? We may be surprised as we end up with more friends… and a more diverse set of ideas to consider.

And maybe, just maybe, this rubble can become the building blocks of a stronger democracy, and stronger communities.

Sharon Kniss is the Director of Education and Training at the Kansas Institute for Peace and Conflict Resolution in North Newton, Kansas.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed